A Visual Guide to FastText Word Embeddings

Word Embeddings are one of the most interesting aspects of the Natural Language Processing field. When I first came across them, it was intriguing to see a simple recipe of unsupervised training on a bunch of text yield representations that show signs of syntactic and semantic understanding.

In this post, we will explore a word embedding algorithm called “FastText” that was introduced by Bojanowski et al. (2017) and understand how it enhances the Word2Vec algorithm from 2013.

Intuition on Word Representations

Suppose we have the following words and we want to represent them as vectors so that they can be used in Machine Learning models.

Ronaldo, Messi, Dicaprio

A simple idea could be to perform a one-hot encoding of the words, where each word gets a unique position.

| isRonaldo | isMessi | isDicaprio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ronaldo | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Messi | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dicaprio | 0 | 0 | 1 |

We can see that this sparse representation doesn’t capture any relationship between the words and every word is isolated from each other.

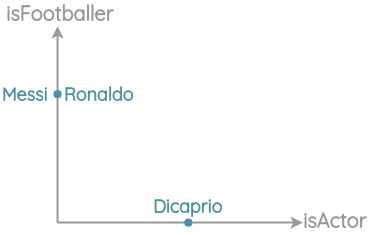

Maybe we could do something better. We know Ronaldo and Messi are footballers while Dicaprio is an actor. Let’s use our world knowledge and create manual features to represent the words better.

| isFootballer | isActor | |

|---|---|---|

| Ronaldo | 1 | 0 |

| Messi | 1 | 0 |

| Dicaprio | 0 | 1 |

This is better than the previous one-hot-encoding because related items are closer in space.

We could keep on adding even more aspects as dimensions to get a more nuanced representation.

| isFootballer | isActor | Popularity | Gender | Height | Weight | … | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ronaldo | 1 | 0 | … | … | … | … | … |

| Messi | 1 | 0 | … | … | … | … | … |

| Dicaprio | 0 | 1 | … | … | … | … | … |

But manually doing this for every possible word is not scalable. If we designed features based on our world knowledge of the relationship between words, can we replicate the same with a neural network?

Can we have neural networks comb through a large corpus of text and generate word representations automatically?

This is the intention behind the research in word-embedding algorithms.

Recapping Word2Vec

In 2013, Mikolov et al. (2013) introduced an efficient method to learn vector representations of words from large amounts of unstructured text data. The paper was an execution of this idea from Distributional Semantics.

You shall know a word by the company it keeps - J.R. Firth 1957

Since similar words appear in a similar context, Mikolov et al. used this insight to formulate two tasks for representation learning.

The first was called “Continuous Bag of Words” where need to predict the center words given the neighbor words.

The second task was called “Skip-gram” where we need to predict the neighbor words given a center word.

Representations learned had interesting properties such as this popular example where arithmetic operations on word vectors seemed to retain meaning.

Limitations of Word2Vec

While Word2Vec was a game-changer for NLP, we will see how there was still some room for improvement:

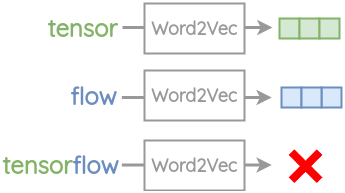

Out of Vocabulary(OOV) Words

In Word2Vec, an embedding is created for each word. As such, it can’t handle any words it has not encountered during its training.

For example, words such as “tensor” and “flow” are present in the vocabulary of Word2Vec. But if you try to get embedding for the compound word “tensorflow”, you will get an out of vocabulary error.

Morphology

For words with same radicals such as “eat” and “eaten”, Word2Vec doesn’t do any parameter sharing. Each word is learned uniquely based on the context it appears in. Thus, there is scope for utilizing the internal structure of the word to make the process more efficient.

FastText

To solve the above challenges, Bojanowski et al. (2017) proposed a new embedding method called FastText. Their key insight was to use the internal structure of a word to improve vector representations obtained from the skip-gram method.

The modification to the skip-gram method is applied as follows:

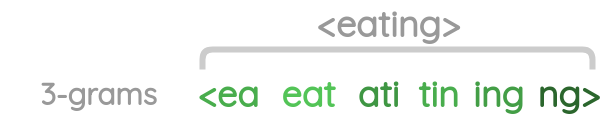

1. Sub-word generation

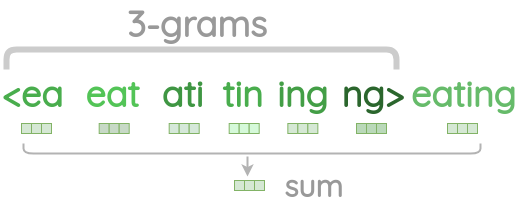

For a word, we generate character n-grams of length 3 to 6 present in it.

- We take a word and add angular brackets to denote the beginning and end of a word

- Then, we generate character n-grams of length n. For example, for the word “eating”, character n-grams of length 3 can be generated by sliding a window of 3 characters from the start of the angular bracket till the ending angular bracket is reached. Here, we shift the window one step each time.

Thus, we get a list of character n-grams for a word.

Examples of different length character n-grams are given below:

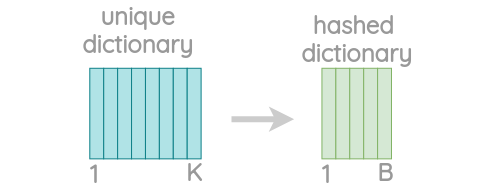

Word Length(n) Character n-grams eating 3 <ea, eat, ati, tin, ing, ng> eating 4 <eat, eati, atin, ting, ing> eating 5 <eati, eatin, ating, ting> eating 6 <eatin, eating, ating> Since there can be huge number of unique n-grams, we apply hashing to bound the memory requirements. Instead of learning an embedding for each unique n-gram, we learn total B embeddings where B denotes the bucket size. The paper used a bucket of a size of 2 million.

Each character n-gram is hashed to an integer between 1 to B. Though this could result in collisions, it helps control the vocabulary size. The paper uses the FNV-1a variant of the Fowler-Noll-Vo hashing function to hash character sequences to integer values.

2. Skip-gram with negative sampling

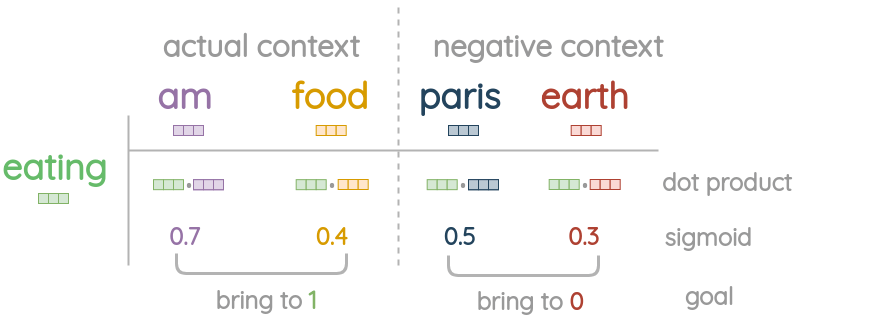

To understand the pre-training, let’s take a simple toy example. We have a sentence with a center word “eating” and need to predict the context words “am” and “food”.

First, the embedding for the center word is calculated by taking a sum of vectors for the character n-grams and the whole word itself.

For the actual context words, we directly take their word vector from the embedding table without adding the character n-grams.

Now, we collect negative samples randomly with probability proportion to the square root of the unigram frequency. For one actual context word, 5 random negative words are sampled.

We take dot product between the center word and the actual context words and apply sigmoid function to get a match score between 0 and 1.

Based on the loss, we update the embedding vectors with SGD optimizer to bring actual context words closer to the center word but increase distance to the negative samples.

Insights from the Paper

FastText improves performance on syntactic word analogy tasks significantly for morphologically rich language like Czech and German.

word2vec-skipgram word2vec-cbow fasttext Czech 52.8 55.0 77.8 German 44.5 45.0 56.4 English 70.1 69.9 74.9 Italian 51.5 51.8 62.7 FastText has degraded performance on semantic analogy tasks compared to Word2Vec.

word2vec-skipgram word2vec-cbow fasttext Czech 25.7 27.6 27.5 German 66.5 66.8 62.3 English 78.5 78.2 77.8 Italian 52.3 54.7 52.3 Using sub-word information with character-ngrams has better performance than CBOW and skip-gram baselines on word-similarity task. Representing out-of-vocab words by summing their sub-words has better performance than assigning null vectors.

skipgram cbow fasttext(null OOV) fasttext(char-ngrams for OOV) Arabic WS353 51 52 54 55 GUR350 61 62 64 70 German GUR65 78 78 81 81 ZG222 35 38 41 44 English RW 43 43 46 47 WS353 72 73 71 71 Spanish WS353 57 58 58 59 French RG65 70 69 75 75 Romanian WS353 48 52 51 54 Russian HJ 69 60 60 66 FastText is 1.5 times slower to train than regular skipgram due to added overhead of n-grams.

Implementation

To train your own embeddings, you can either use the official CLI tool or use the fasttext implementation available in gensim.

Pre-trained word vectors trained on Common Crawl and Wikipedia for 157 languages are available here and variants of English word vectors are available here.

References

Citation

@online{chaudhary2020,

author = {Chaudhary, Amit},

title = {A {Visual} {Guide} to {FastText} {Word} {Embeddings}},

date = {2020-06-21},

url = {https://amitness.com/posts/fasttext-embeddings.html},

langid = {en}

}