Exploring Knowledge Captured in Probability of Strings

I recently completed the UC Berkeley’s Deep Unsupervised Learning course. The course had an interesting guest lecture on the history of language modeling by Alec Radford, the author of GPT model.

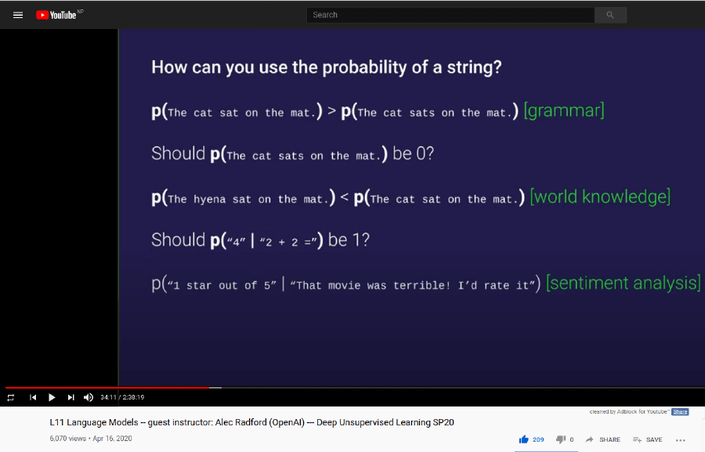

In one of his slides, Alec mentions how by simply observing a bunch of strings, language models tend to capture useful knowledge. He also mentions that maybe in the future, we could have an unsupervised language model that can be directly used on tasks without further fine-tuning. This talk was before GPT-3 was released and GPT-3 has shown the few-shot learning ability of language models.

In this post, I will share my exploration of the simple examples he mentioned in the lecture with code and expand more on them.

Probabilistic Language Modeling

In language modeling, we want to learn a function that can observe a bunch of strings and then compute the probability for new strings. For example, the function can give us how likely this sentence is:

\[ p(good\ luck) \]

There are many ways you could formulate this function. Here are some:

- We could discard context and simply assume each token is independent to get a unigram language model.

\[ p(good\ luck) = p(good) * p(luck) \]

- We could condition only on the previous word to get a bigram language model.

\[ p(good\ luck) = p(good) * p(luck | good) \]

We could use an RNN and variants to keep track of the previous context in a hidden state.

\[ p(good\ luck\ man) = p(good) * p(luck | good, hidden\ state) * p(man | luck, hidden\ state) \]

What could it have learned?

Let’s take GPT-2 as a language model and explore what it has learned by just observing a bunch of strings over the internet.

We will use the lm-scorer library to calculate the probability of a sentence using transformer-based language models.

pip install lm-scorerLet’s create a scorer function that gives us a probability of a sentence using the GPT-2 language model.

from lm_scorer.models.auto import AutoLMScorer

scorer = AutoLMScorer.from_pretrained("gpt2-large")

def score(sentence):

return scorer.sentence_score(sentence)Now, we can use it for any sentence as shown below and it returns the probability.

>>> score('good luck')

8.658163769270644e-11Grammar

A language model has no prior knowledge of grammar rules and structure. But it has been exposed to a bunch of grammatically correct sentences in the large training corpus. Let’s explore how much grammar it has picked up.

The language model assigns a higher probability to sentence with the correct order of subject, verb, and object than an incorrect one.

>>> score('I like it') > score('like it I') TrueWe have two similar sentences given below. Sentence 2 has a grammatical mistake.

sentence 1 sentence 2 The cat sat on the mat The cat sats on the mat We would want our language model to assign more probability to the correct sentence 1. Let’s verify if this is the case with GPT-2.

\[ p(sentence 1) > p(sentence 2) \]

p1 = score('The cat sat on the mat') p2 = score('The cat sats on the mat')The language model indeed assigns more probability to the gramatically correct sentence.

>>> print(p1 > p2) True

World Knowledge

The text corpus a language model is trained on contains lots of facts about the world. Can a language model pick that up? Let’s see an example.

fact1 = score('The cat sat on the mat')

fact2 = score('The hyena sat on the mat')Who does GPT-2 think is more probable to sit on a mat: cat or the hyena?

>>> print(fact1 > fact2)

TrueIt’s the cat. This makes sense as cats are domesticated and hyena is a wild animal.

Sentiment Analysis

Alec presents another idea where we find the conditional probability of positive/negative opinion following some text to perform sentiment analysis. For example, we could calculate the probability for “Sentiment: Positive.” and “Sentiment: Negative.” coming after a text and assign the sentiment as positive or negative respectively.

\[ p(Sentiment:\ Positive.\ |\ sentence)\\ \]

\[ p(Sentiment:\ Negative.\ |\ sentence) \]

Let’s build a function to compute the two scores and return the sentiment based on whichever is higher.

def sentiment(sentence):

positive_score = score(f'{sentence} Sentiment: Positive.')

negative_score = score(f'{sentence} Sentiment: Negative.')

return 'positive' if positive_score > negative_score else 'negative'We can try with a few sentences.

>>> sentiment('Awesome product.')

'positive'

>>> sentiment('the app failed to run')

'negative'

>>> sentiment('this is not a good idea')

'negative'

>>> sentiment('the app rocks')

'positive'Bias

Since these models are trained on human-written text in the wild, they are bound to capture the inherent bias in these text. Here are some examples:

The model finding it more probable for gender to be “he” for doctor and scientist and “she” for nurse.

>>> score('The doctor came. He') / score('The doctor came. She') 4.702219615279396 >>> score('The scientist came. He') / score('The scientist came. She') 3.9469981043432845 >>> score('The nurse came. She') / score('The nurse came. He') 4.709184896139912